Mark Cantor was featured on the front page of the April 6 issue of Missouri Lawyers Weekly. The article was also featured on the Missouri Lawyers Weekly website: https://molawyersmedia.com/2015/04/06/lawmakers-lawyers-support-regulation-of-legal-funding-industry/

St. Louis personal injury plaintiffs’ attorney Mark Cantor of Cantor Injury Law advises against the use of funding companies settlement loans in Missouri. He has gone so far as to put that advice in his clients’ contracts. Photo by: KAREN ELSHOUT

Lawmakers And Lawyers Support The Regulation Of The Legal Funding Industry

It’s a situation many plaintiffs’ attorneys have seen. There’s been a car accident, a fall, a fight. The client can’t work anymore. There are kids to feed and medical bills to pay. Litigation is moving forward, but not fast enough. So the client calls a civil litigation funding company and, if approved, within 24 hours has enough money to tide them over. But they may not be aware of the true cost.

“Clients are in such dire straits. They have nowhere else to turn,” said Rep. Elijah Haahr, R-Springfield and author of one of several proposed bills in the Missouri Legislature that would regulate the civil litigation funding industry.

Haahr has firsthand experience with legal funding. He’s a personal injury attorney with the firm of Aaron Sachs & Associates in Springfield. He’s dealt with the companies on several cases, and he said it can be difficult.

“We generally discourage our clients from taking [the loans] out,” Haahr said.

Civil litigation funding companies offer to loan plaintiffs money based on what they might get from a settlement or judgment in their case. However, the interest rates can be ten times higher than the average loan, and some compound monthly. Over the course of repayment the client can owe two to three times the loan’s original value.

Clients do not owe the money if they lose their case, but they are obligated to pay it back, plus fees, if they win a verdict or settle their case out of court.

Eric Schuller, the director of government and community affairs for Oasis Legal Financing, a legal funding company that operates in 44 states, including Missouri, and the District of Columbia, said the service his company provides isn’t a settlement loan.

“They owe us nothing,” said Schuller. “It is the purchase of an asset; the settlement.”

“They owe us nothing. It is the purchase of an asset; the settlement.”– Eric Schuller, the director of government and community affairs for Oasis Legal Financing

His company charges “fees,” not “interest,” and those fees are clearly stated in the contract, he said. However, in Illinois, Missouri and South Carolina the company does charge interest, according to its website.

It’s an issue of semantics, according to David Winton, who represents the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Institute for Legal Reform.

“They happen to be non-recourse loans, but they are still loans,” he said.

When he looks over the contracts issued to his clients by legal financing companies, Haahr said the document calls it a loan. As does Oasis’ website, which states clearly that its services are not a loan, except in Illinois and Missouri. And as a loan company, Oasis and its ilk should be regulated much like any other financial institution or short-term loan provider, Haahr said.

“There’s really no regulation,” he said.

Few Regulations

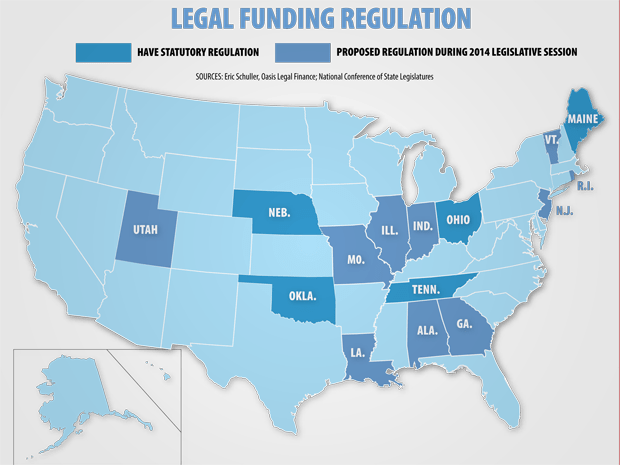

Only five states – Maine, Ohio, Nebraska, Oklahoma and Tennessee – regulate legal funding companies, according to Schuller. Tennessee is the only state to cap the percentage rate on the loans – at 10 percent annually. The other states have legislated to ensure consumers are aware of the total cost of the loan every six months, and the maximum amount it could cost at the full term of the loan. There are also provisions to limit the companies’ involvement with the attorney and the litigation.

During the 2014 legislative session, 12 states attempted to regulate the industry, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Few were successful.

The industry makes some attempt to regulate itself through organizations such as the American Legal Finance Association, which represents 43 members, or about 90 percent of the legal funding market, according to spokesman Jack Kelly. ALFA advises its members of best practices that are very similar to existing state regulation: stay out of the litigation, tell customers up front what they will owe, be honest.

But there is no mention of a cap in percentage rates or fees. After all, the companies are taking on a great deal of risk, Schuller said. Schuller estimated that in some states Oasis’ loss rate was around 25 percent. So the fact that over the course of 18 months a $1,000 funding agreement can easily become $1,800 is not unreasonable, he said.

Too much regulation would prevent Oasis from providing a necessary service, Schuller said. By capping interest rates and classifying the transaction as a loan, the Legislature might add Missouri to the states where Oasis does not operate. Due to regulation, from statute or caselaw, it is not possible for Oasis to do business in a profitable manner or to the benefit of the consumer, Schuller said.

Legislation

Four pieces of legislation have been filed in the Missouri Legislature this session that seek to regulate, and in one case abolish, the civil litigation funding industry. The only one to be voted out of committee thus far is Haahr’s.

Haahr does not think the practice should be banned all together, but he said there should be some oversight. His bill would bar attorneys and the funding companies from having an ongoing relationship and says the funding companies cannot receive any kickbacks or referral fees from the attorney. The bill also dictates that the funding company can’t make decisions about the litigation. Haahr’s bill also caps the interest rates at 21 percent.

The funding industry, however, supports a bill sponsored by Rep. Tony Dugger, R-Hartville, that would require attorneys be notified if their client partakes in civil litigation funding and would make sure terms of the loan are made clear to consumers. Dugger’s bill, however, doesn’t cap interest percentages or fees.

That bill was heard in committee but hasn’t received a vote.

Winton said that approach legitimizes “an industry that has no consumer protections.”

“These are individuals that are fairly desperate, and an industry that is highly predatory,” Winton said.

“These are individuals that are fairly desperate, and an industry that is highly predatory.”– David Winton, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Institute for Legal Reform

Leery of the high fees that he says can grow to 200 percent as they are compounded, St. Louis personal injury plaintiffs’ attorney Mark Cantor of Cantor Injury Law also advises against the use of funding companies. He went so far as to put that advice in his clients’ contracts.

“Loan companies add an inefficiency to the system. They charge a large, unjust interest rate,” Cantor said.

Although funding companies ultimately come up with their own value for cases, they speak to the attorney as part of the investigation, Schuller said. They also get police reports, witness statements and other basic information.

“They’re not making the loans off the cuff,” Haahr said.

Influencing Litigation

In Missouri, settlement loans can drag out cases that have the potential to settle prior to trial, creating a potential burden on attorneys as well. Clients are thinking about the amount of the loan, not necessarily their best outcome, Haahr said. A client might turn down a reasonable settlement and opt to proceed to trial because the settlement won’t cover their funding agreement.

“They have a tremendous amount of influence,” Winton said.

And if the client holds out for a jury verdict and they lose? Well, the attorney loses too. If he or she has taken the case on a contingency fee basis, they won’t get paid. In addition, if there are medical bills associated with the case, the doctor or hospital is not likely to get paid either. Which means of the three most common liens on cases, the two entities that provided services won’t be compensated.

“The people left unpaid are the physician, the attorney, and the loan company. But [the loan company] undertook that risk,” said Cantor.

Missouri law provides that attorneys get paid first, followed by expenses, and the doctors’ fees.

That is exactly what happened in a case of Cantor’s. Plaintiff Rebecca Wooten needed help covering basic expenses after she injured her neck and back in a car accident. Cantor said she turned down settlement offers because of a funding loan. Earlier settlement offers weren’t going to be enough to pay the attorneys’ fees, the medical bills and what she owed the funding company. She needed a larger judgment from the jury.

She didn’t get it. In January, a St. Louis County jury found in favor of the defendant in the car crash. However, under the funding agreement, she isn’t liable for the loan.

“Why not go for more? Because they have nothing to lose,” Cantor said, adding that he didn’t fault his client for taking out the loan. He said Wooten did not wish to be interviewed.

Regulation or no, clients can still get in over their head. Cantor recounted one such incident where he was representing a plaintiff on a workers’ compensation case. His client won, but the judgment was not enough to cover the liens and contingencies the client needed to pay.

Cantor could have taken his fee and walked away, but his client came to the attorney for help with the debt. The only recourse Cantor’s client had was to leverage his case in order to get the loan company to forgive some of the debt, even if it meant the attorney would not be paid.

“We called the loan company and threatened to forgive the judgment and walk away,” Cantor said.

Ultimately, that worked in his client’s favor. And the tactic seems to be one of the few ways to make sure the client, the attorney, and the doctors get paid.

“At the threat of a jury trial that can be lost, the companies will reduce the loan,” Cantor said.